Plague on Reefs: Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease

If you have ever touched the waters of the Florida Keys you have been in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, which is home to North America’s only living barrier reef and the world’s third largest. The reef provides services to local species and human society alike, from supporting important fish species, protecting the coast from storm surges and erosion, playing a vital role in nutrient cycles, and providing a world-famous backdrop for recreation and tourism activities. Unfortunately, the coral reef tract that spans nearly 400 miles of Florida’s southeast coast faces numerous threats to its existence, including one of the most severe coral disease outbreaks ever recorded.

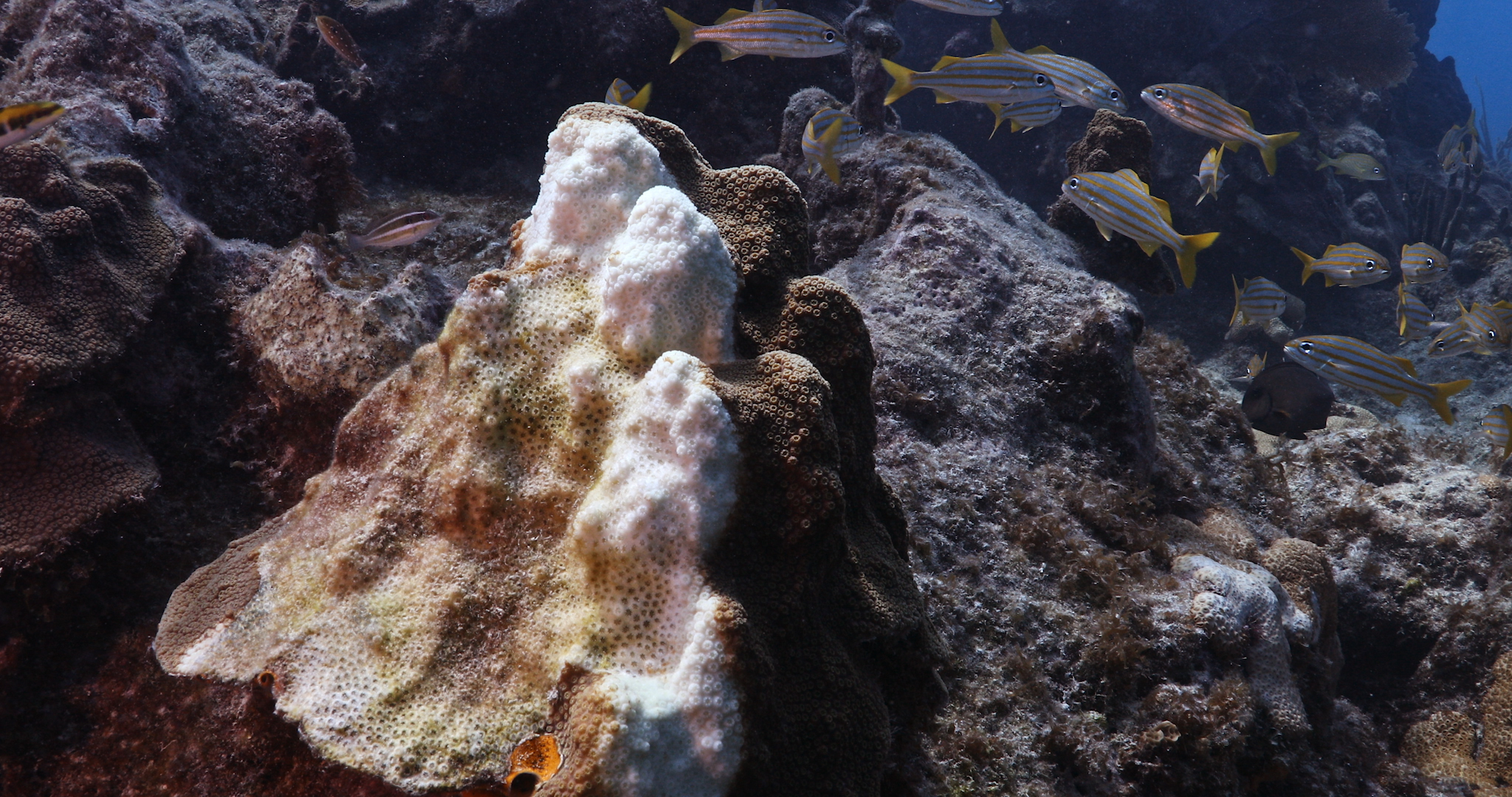

Called Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD), it is characterized by the disappearance of tissue from a coral’s skeleton. Unlike coral bleaching, it does not appear SCTLD is reversible. Experts believe the outbreak began near Virginia Key in Miami-Dade County in 2014, spreading to other areas of the Florida reef, both north and south. Scientists are still trying to understand the disease’s cause and nature, but it appears to be bacterial, transmitted to other coral colonies by water current circulation and direct physical contact, and may be spread faster by diving equipment that has not been completely sanitized between uses. In some species of coral, mortality rates (the number of infected individuals that do not survive) of SCTLD can reach 100%. Compounded by other challenges like increasing water temperatures, ocean acidification, coastal development, and both chemical and physical pollution, disease can be made much worse and pose a greater risk to ecosystems and the communities that rely on them.

While coral disease outbreaks have been observed all over the world, none have had the geographic spread, long duration, mortality rates, and species affected in the way SCTLD has. Since 2014 the disease has continued its rapid spread, affecting more than half of the Florida Reef Tract (a total area of more than 96,000 acres of reef), including at least 20 of 45 species of coral that live along the tract – five of those 20 species are listed under the Endangered Species Act. The outbreak is not only an ecological challenge but one of human concern as well as it threatens reefs that play a vital role in tourism, the state of Florida’s most valuable industry.

But, conservation organizations and government agencies are fighting back. The state of Florida’s Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) along with nonprofit, governmental, university, and citizen partners has set out to educate Florida’s residents and visitors of the disease, track its spread and study both its effects and possible treatments, and attempt to restore areas of the reef tract. Specific to the Florida Keys, here’s what NOAA, the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation, and the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary are doing to help with coral restoration and recovery in the sanctuary:

In 2019, the sanctuary launched Mission: Iconic Reefs, one of the largest investments in reef restoration in the world, to restore corals at seven iconic reef sites in Florida Keys waters;

Founded in 2019, Islamorada Conservation and Restoration Education (I.CARE) engages citizen divers to help outplant and monitor Mote-supplied coral fragments onto Islamorada’s reefs to restore ecological health to these reefs.

In 2018, the sanctuary and the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation partnered to launch Goal: Clean Seas Florida Keys, a program dedicated to the removal of underwater marine debris in reefs throughout Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary to improve reef resilience.

Coral disease present in Looe Key in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Photo Credit: Nick Zachar