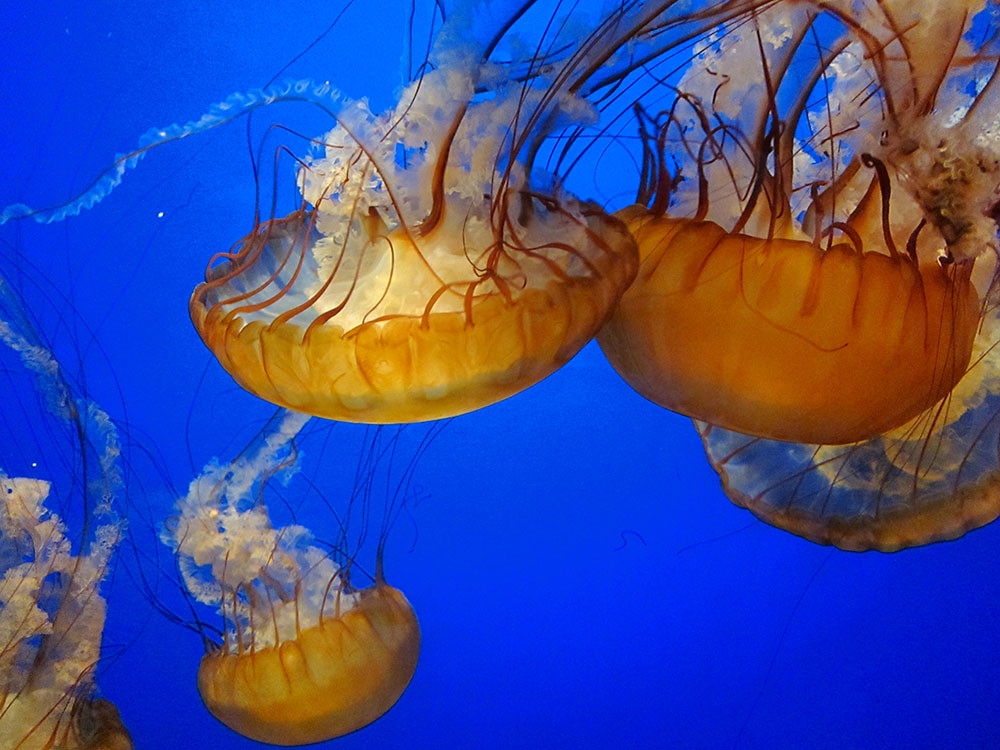

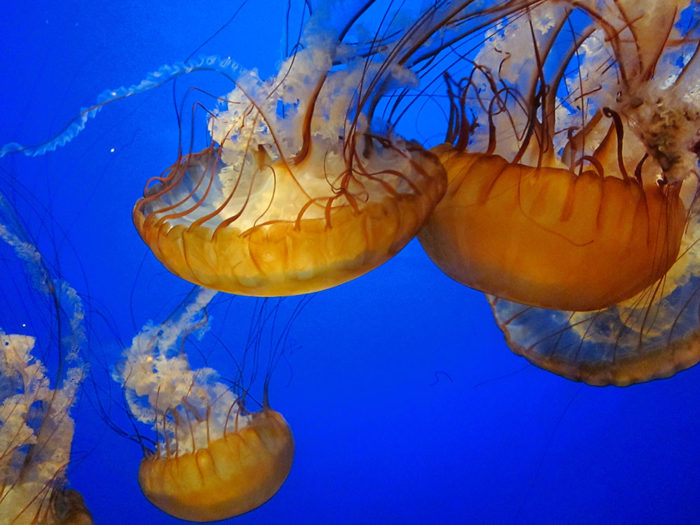

Creature Feature: Pacific Sea Nettle

Photo credit: Zug Zwang

Known to be both beautiful and mysterious, this week’s Creature Feature is none other than the Pacific Sea Nettle, a recognizable species of jellyfish found in the Pacific ocean, including all of America’s west coast national marine sanctuaries.

Appearance

The Pacific Sea Nettle is known for its red-brown bell, long, spiraling arms, and thin tentacles. The bell can grow to a maximum of nearly 30 inches in diameter while the trailing arms can reach 12 to 15 feet in length!

At first glance, there might not seem to be much to these creatures, but their bodies are complex and interesting. Given they are jellyfish, their bell (or body) is made of three layers: the outer layer (epidermis); a thick, gelatinous middle layer(mesoglea); and the innermost layer (gastrodermis). Like all other jellyfish, the Pacific sea nettle is mostly water with a basic nervous system that allows the animal to respond to stimuli like light and smell. Fun fact: the sensory organs used to detect light are called ocelli, also known as a simple eye.

Diet & Life History

The Pacific sea nettle is carnivorous and eats simple and easy-to-catch animals: zooplankton, larval fishes, crustaceans, eggs, and sometimes other jellies. But without a mouth, how do these jellies eat? Not by filtration like you might expect, but more actively through a process that’s a little like that of a venus flytrap. With a single opening that allows food to enter and waste to exit the body, the Pacific sea nettle’s thin tentacles sting and paralyze prey, while the longer, spiraling arms trap and transport the food to the bell. The good news is that the Pacific sea nettle’s sting is lethal to its prey but not to people, however, its sting is still quite painful to humans.

Given they rely on plankton and larva for their diet, Pacific sea nettles follow their prey up and down in the water column in response to the light cycle. Some individuals can travel more than 3,600 vertical feet each day by squeezing their bell and pushing water out, allowing them to resist currents!

Pacific sea nettles start as tiny eggs that hatch and grow into planula (more free-swimming larva). Once they reach the planula stage, females release the larva into the ocean where they drift until they reach a solid, stable surface to attach to. From there, they grow into polyps that makes identical copies of itself through a process called budding, and the cloned polyps are released into the ocean and metamorphize as they grow, developing their distinct bells, arms, and tentacles. An adult jellyfish is called a medusa, named after the mythological creature they resemble. The Smithsonian offers an illustration of the typical jellyfish lifecycle here.

Habitat

Pacific sea nettles are found in the Pacific ocean’s open waters, ranging from Alaska to Japan, and from California (and sometimes Mexico) to Canada. They are a foundational component of marine food webs in the Pacific ocean, serving as prey for marine birds, sea turtles, fish, and even marine mammals. Scientists also believe these jellyfish may serve as both a vehicle and a food source for hitchhiking larval and juvenile crabs that can withstand or avoid the stinging tentacles.

Reproduction

Pacific sea nettles are able to reproduce both sexually and asexually. Sexual reproduction occurs when females capture sperm drifting through the ocean that fertilizes eggs they have produced, and this reproductive strategy helps create genetic diversity. The asexual component of reproduction comes during the polyp phase when budding (cloning) occurs and genetically identical individuals are released into the ocean.

Population Status

Historically, healthy populations of larger animals kept jellyfish populations in check. However, jellyfish populations worldwide, including Pacific sea nettles, are growing at an alarming rate, suggesting food webs are out of balance due to human activity.