Sea Wonder: Manta Ray

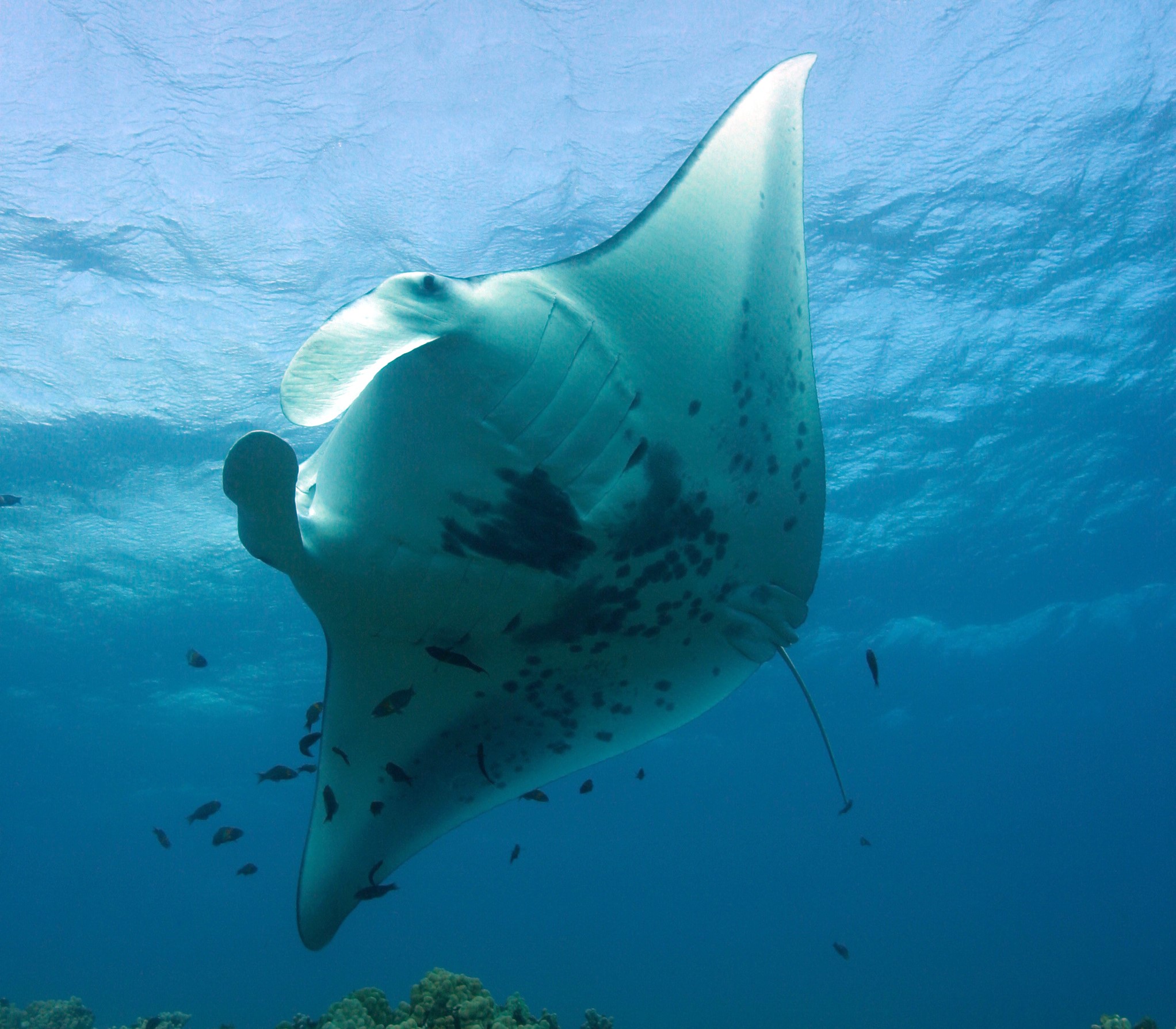

A manta ray glides through Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary. Photo credit: Ed Lyman

Manta rays (Mobula birostris) are majestic, mysterious, and one of the largest fishes in the world’s ocean. For centuries, mantas have captured the human imagination, making their way into cultural lore and traditions.

DESCRIPTION

Manta rays are members of the cartilaginous fish family and the largest species of ray in the entire world. They have a distinctive, diamond-shaped body with long, wing-like pectoral fins, ventrally located gill slits, and characteristically wide mouths that have a lobe on each side that help channel water in. Their wingspans can reach as many as 29 feet long and they can weigh upwards of 3,600 pounds when fully grown! Females tend to be slightly smaller than males. There are two distinct species of manta recognized by science: the giant manta ray, which is oceanic, and the reef manta, which lives closer to the coast.

Manta rays have two distinct colorations that are determined by genetics and where they live: chevron, a darker black back and white belly, and all black. They are the only vertebrate animals that have three sets of paired appendages: two pectoral fins, two sets of gills, and two lobes that extend from the mouth. In addition to their impressive body size, giant manta rays have the biggest brains of any known fish in the ocean.

DIET & HABITAT

Manta rays are passive filter feeders, swimming with their gaping mouths open and filtering plankton and small fish from the water that flows through. Food that enters the mouth is filtered by organs called gill rakers before being swallowed whole. On rare occasions, they will perform barrel rolls while feeding to maximize their prey intake. A full-grown adult manta can eat as much as 60 pounds of food each day, which can equal millions of microscopic plankton!

Mantas are generally found in tropical, subtropical, and temperate waters worldwide. They are commonly seen offshore and near productive coastlines, and they are migratory throughout the year. Within the National Marine Sanctuary System, we see manta rays in or near Flower Garden Banks, Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale, American Samoa, Channel Islands, Florida Keys, Gray’s Reef, and Stellwagen Bank national marine sanctuaries.

LIFE HISTORY

Manta rays are generally solitary throughout their lives, though they do gather for feeding and mating opportunities. A group of manta rays is called a squadron.

Giant manta rays have one of the lowest reproductive rates of all cartilaginous fish, giving birth to one pup every two to five years. A manta pregnancy can last nearly a year. They are ovoviviparous reproducers, meaning the embryo develops in the mother’s uterus before being born live. Pups are born with their wings wrapped around their body to allow easier passage through the birth canal. Manta rays reach maturity when they are fully grown at between eight and 10 years old. Scientists believe mantas can live to be at least 50 years old, though we still don’t know much about their growth and development throughout their lifespans.

THREATS & CONSERVATION

Manta rays are listed as vulnerable by the IUCN Red List and are listed under the Endangered Species Act and and CITES Appendix II. Threats to manta ray populations include bycatch, marine debris, vessel strikes, and environmental changes that affect their habitats and prey. Fortunately, their appeal to SCUBA divers and other tourism operations as a charismatic species makes mantas more valuable alive than to fishers.

A manta ray and two remoras swimming in Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Photo credit: Beata Lerman