Celebrating Wave Makers for Women’s History Month: Dr. Eugenie Clark “The Shark Lady”

Dr. Eugenie Clark with a belted sandperch. Photo by Mote Marine Laboratory.

Dr. Eugenie Clark, also known as “the Shark Lady”, was a true wave maker in marine science. An ichthyologist (fish scientist) by trade and the founding director of what is now Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium in Florida, she paved the way for women and girls in science. As part of Women’s History Month, we honor her life and her legacy.

Dr. Clark (1922-2015) was born and raised in New York City. Many trips to the local aquarium throughout her childhood sparked her curiosity and passion for marine science, specifically fish. Her mother’s Japanese heritage and culture – specifically the importance of the sea – is also a part of Dr. Clark’s upbringing that she credited as influential in setting her life’s course.

Genie Clark received her bachelor’s degree in zoology from Hunter College in New York City in 1942, and throughout her undergraduate career she studied at the University of Michigan Biological Station and worked as a chemist with the Celanese Corporation. After graduating, she immediately continued her educational journey, earning a master’s in zoology in 1946 and her doctorate of zoology in 1950 from New York University. After earning her master’s, she served as a research assistant at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, where she first learned to SCUBA dive. Her Ph.D. research focused on the live bearing production of platys and swordtail fish. She also worked at what is now the Wildlife Conservation Society, the American Museum of Natural History in New York, and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute in Massachusetts.

Dr. Clark’s research career took her all over the world to learn more about the ocean and pave the way for future female scientists. A Fulbright scholarship award allowed her to conduct research at the Marine Biological Station on the northern Red Sea Coast of Egypt. She also conducted research in Micronesia, Guam, the Marshall Islands, the Palau islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the Caroline Islands. Her work in these places not only allowed her to explore her passion but also advanced our understanding of fishes in the world’s ocean.

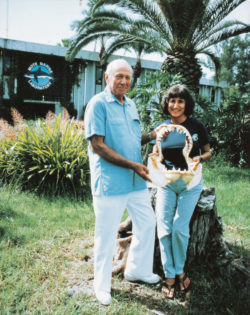

Mr. Mote and Dr. Eugenie Clark with a shark jaw in front of Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida. Photo by Mote Marine Laboratory.

Through scientific publications and books, Dr. Clark was able to share both her findings and her life experiences. Her first book, Lady with a Spear, published in 1953, detailed her time in Egypt and her discovery of many Red Sea fish. One of her discoveries was the Red Sea Moses sole (Pardachirus marmoratus) which led to another major discovery: it is a fish that produces a natural shark repellent. Her book received interest from Anne and William H. Vanderbilt, who would eventually fund her next endeavor: building a new marine laboratory. In 1955, Dr. Clark founded Cape Haze Marine Laboratory in Florida, which is now known as Mote Marine Laboratory. This now full-fledged and well-known research facility began as a one-woman operation ran by Dr. Clark. Along the way, she worked with local fishermen and the lab became a place Dr. Clark could engage with the public on marine conservation, continue her research, and dispel myths about sharks. She served as the organization’s executive director until 1967.

In 1968, Dr. Clark joined the faculty at the University of Maryland College Park where she taught marine biology until her retirement in 1992. She published her second book, The Lady and the Sharks, in 1969 and authored or co-authored more than 175 scientific articles throughout her career. Dr. Clark was an avid diver until 2014, conducting 72 deep submersible dives and countless SCUBA excursions throughout her lifetime.

On February 25, 2015, at 92 years old, Dr. Clark passed away, leaving behind an incredible legacy that includes her accomplishments as an ichthyologist, as the founder of an institution for scientific discovery and public engagement, and as a trailblazer for women and girls in the sciences. Even decades later, her work on sharks and fish continues to be influential. Some examples of her accomplishments and discoveries throughout her career include:

Discovering that some sharks do not have to swim continuously to breathe. Her discovery of sleeping sharks was a tremendous contribution to understanding shark biology and behavior and informed her “Shark Lady” nickname.

She was the first person to use operant conditioning to train sharks to press targets and perform other behaviors. This is how we train mammals like dogs and dolphins, but doing so with fish was groundbreaking and continues to inform our understanding of intelligence in animals.

She was the first person to develop “test tube” babies in female fish.

Through her research and outreach, Dr. Clark dispelled many persistent myths and misconceptions people held about sharks. Her efforts improved public perceptions of the species, which led to important conservation efforts and an appreciation for animals that are otherwise misunderstood.

A Japanese-American woman, she paved the way for women in science, showing how much women had to contribute to the male-dominated institution of science.

Throughout her career, Dr. Clark received many awards and honors including three honorary degrees and awards from the National Geographic Society, the Explorers Club, the Underwater Society of America, the American Littoral Society, the Gold Medal Award of the Society of Women Geographers, and the President’s Medal of the University of Maryland.

Women’s History Month started in the 1970s as a localized, week-long celebration in California that aimed to recognize the contributions of women to society. As the idea of Women’s History Week caught on, the National Women’s History Project (now the National Women’s History Alliance) led a coordinated effort for states to declare the whole month of March Women’s History Month. In 1981, Congress passed Public Law 97-28, which authorized and asked the President to formally declare Women’s History Week. In 1982, President Jimmy Carter issued a Presidential Proclamation declaring the week of March 7th Women’s History Week and by 1986, there was wider support for a national-level recognition of women’s history in America. The National Women’s History Project petitioned Congress to expand Women’s History Week to span the entire month of March and in 1987, Congress declared the first Women’s History Month. The rest is history.

Dr. Eugenie Clark diving with a bull shark in Mexico in 1974. This shark was one of the mysterious “sleeping” sharks that she studied in underwater caves of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Photo by David Doubilet.